Enjoy life

Those are more than a saying on every one of our corks.

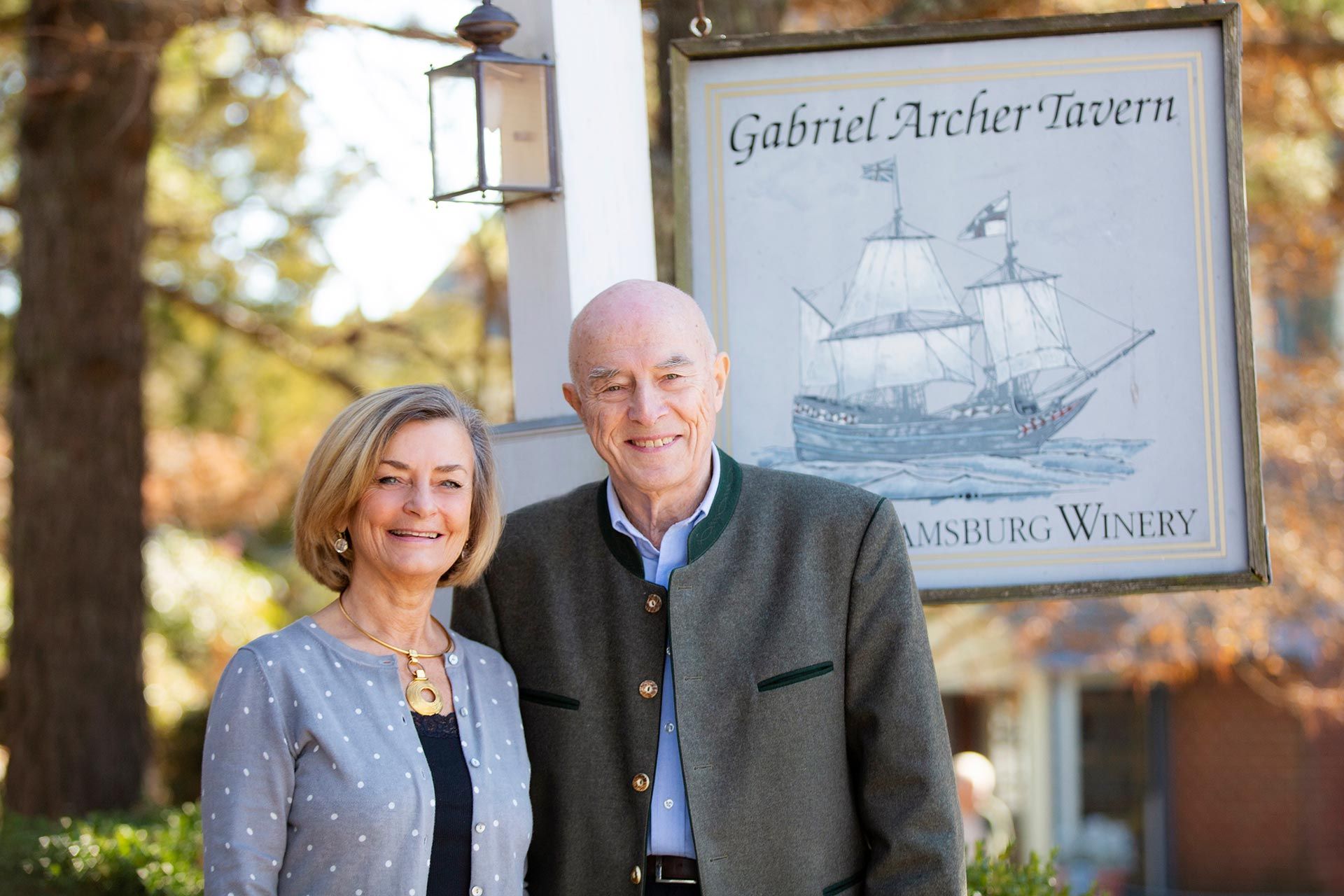

To fully appreciate the ambitious goal to create a home an ocean away, in a place with free air and a pleasing climate to raise a family and start a business in an industry where most doubted we would succeed, we start with a look at history. It’s a timeline that began nearly a century before my late wife, Peggy, and I began the exhaustive search for a farm where we could plant grape vines.

While the first grapes were planted as early as 1609, wine and Virginia wasn’t anyone’s ideal pairing. I can’t say I wasn’t daunted by the challenge, but I accepted it, knowing no worthwhile project is ever easy. I was neither a winemaker nor a viticulturalist, but I had a firm grasp on both and the business acumen to persist.

Like all of us, I was shaped by events that happened well before my birth, a history that dates back to 1900. No, I wasn’t born until 1942, but many of the people who influenced me as a young boy — my father, George; my grandmother, Scarlett, and my great uncle — were shaped by the times that included two world wars. My Uncle Henry was a World War I veteran and one of the most genuine people I’ve ever met. What he saw as a 24-year-old soldier, the stories he relayed to my brother and me about a fractured society give me perspective to life in the modern day, which is not quite as bad as what some of the members of my family lived through.

The events that shaped them shaped me, a boy born in Brussels, Belgium in wartime Europe. The simplicity of conversations with them, many held outdoors in the fresh air underneath a canopy of trees, wasn’t lost on me. Many today would consider the world my family grew up in as primitive. Forget computers. My grandmother didn’t grow up with a phone and rarely knew of telegraph. My father and I remember a world with faces pressed against storefront glass watching pictures on a screen — the first televisions.

But technology and its evolution all the way up to two people sitting in the same room sending text messages back and forth didn’t change my core belief shaped by my roots. The best communication is eye to eye, face to face. It’s not through a device. We do that best outside in the fresh air or indoors over good food and a glass of wine.

From an early age, I learned that family and family time are precious, worth preserving. We all, too, should be humble enough to walk past a mirror without looking at our own reflection thinking, “I’m important.” We all are born the same way and we all finish in dust.

That set of lessons ingrained in me, I came to the United States as a student finishing high school my senior year followed by the opportunity to study economics and finance at the University of Rochester. I was hungry to achieve in a country where I saw freedom and opportunity. I worked in marketing for an international division of Eastman Kodak while still in college.

The rest of my professional history has been well documented – a move to Switzerland to work at Philip Morris and subsequently head up the creation of the inaugural Marlboro Formula One Racing team. I owe a measure of my success to both at Kodak and as the youngest director of Philip Morris International — Kodak from a formative point of view, Philip Morris from its management.

I stayed with Philip Morris for seven years, seven incredibly rich years. Being involved with Formula One racing was a thrill.

I was never a smoker nor was the president of Philip Morris at that time, for that matter. But when my father developed emphysema, that affected me and my future path. My father, a publisher by trade, was exceptional in so many different ways. His father was an importer of mechanical equipment from the United States that he distributed in Europe. In 1929, he had debt in dollars. Everything collapsed. Banks took over businesses. My father was a very cautious person. You would be after that.

He married my mother, Cornelia, in 1935. While they planned to have no children, my brother, Eric, was followed by me. My mother was a historian who loved taking us to castles and parks. By the time I came to the United States, I had traveled from Sweden to Portugal from Norway to Italy and everything in between.

We did things as a family and those times and their value wasn’t lost on me as a businessman. “I’m working for what?” I asked myself after my father’s diagnosis.

I joined an investment group in Geneva, where every week I was driving back and forth between that city and Beaune, the capital of Burgundy. I learned about the wine world. That’s wasn’t my first introduction to it. Back in 1956, during one of our family trips we visited Périgueux, an epiphany for me.

We were in a white tablecloth restaurant. I was 13; my brother was 15. My father wanted to baptize us in what fine wine and fine food represent. We enjoyed Foie Gras, a delicacy of the French. It was one of those epiphanies that clicked in my brain – rich food with rich wine, the right wine, matter.

Another snippet from my past — when I was at the airport in Paris prepared to catch a flight to Geneva. Wait, I was told, there are no planes in and out due to a fire. The traffic around the city was completely paralyzed — a four-lane highway underneath the airport was blocked in both directions. A short in the electrical wiring was the culprit that impacted the entire system over Europe.

The engineers who designed that airport never thought about what could happen. Don’t trust what’s fashionable. Don’t trust mental projections of fools. Details matter.

Everything matters and explains what came later and why.

Peggy had a disdain for big business, and the decision to be fully independent and forge our own path stemmed from her watching me working nonstop, spending days without seeing our family.

“You should do something you should really like,” she suggested.

We were drawn to Williamsburg, where we had previously visited. After an exhaustive search of 52 farms, we found this one — 300 acres alongside a creek where an agricultural business could blossom, a large parcel of land that we called Wessex Hundred, as the use of “Hundred” to name a property dates back to the Colonial era and describes parcels of land sufficient to support 100 families regardless of actual acreage. With several oversized barns in the middle of the property, amid hundreds of trees impressive in size, with the James River in our view, we went to work on a vision that no one else shared.

The steps to planting our first grapes in 1985, releasing the first wine in 1988 and earning our first Virginia Governor’s Cup in 1990 are detailed in a series of blog posts. Sharing my history and the history that came before that, adds a layer of context that permeates every step along the way of this 40-year journey.

The green space at Wessex Hundred reminds me of the woods where my uncle shared from his youth. The fresh food complemented by quality wine our patrons enjoy sitting under the wisteria at the Gabriel Archer Tavern take me back to that elegant meal in Périgueux.

The snarl at the Paris airport — what a mess you can have on your hands if you fail to account for everything that could happen. Be purposeful and intentional in what you do. We have strived to do that at Wessex Hundred, whether that be in the vineyards, as winemakers or as stewards to the environment.

History is our best teacher. Don’t overlook its wisdom. Learn it and even better, learn from it.

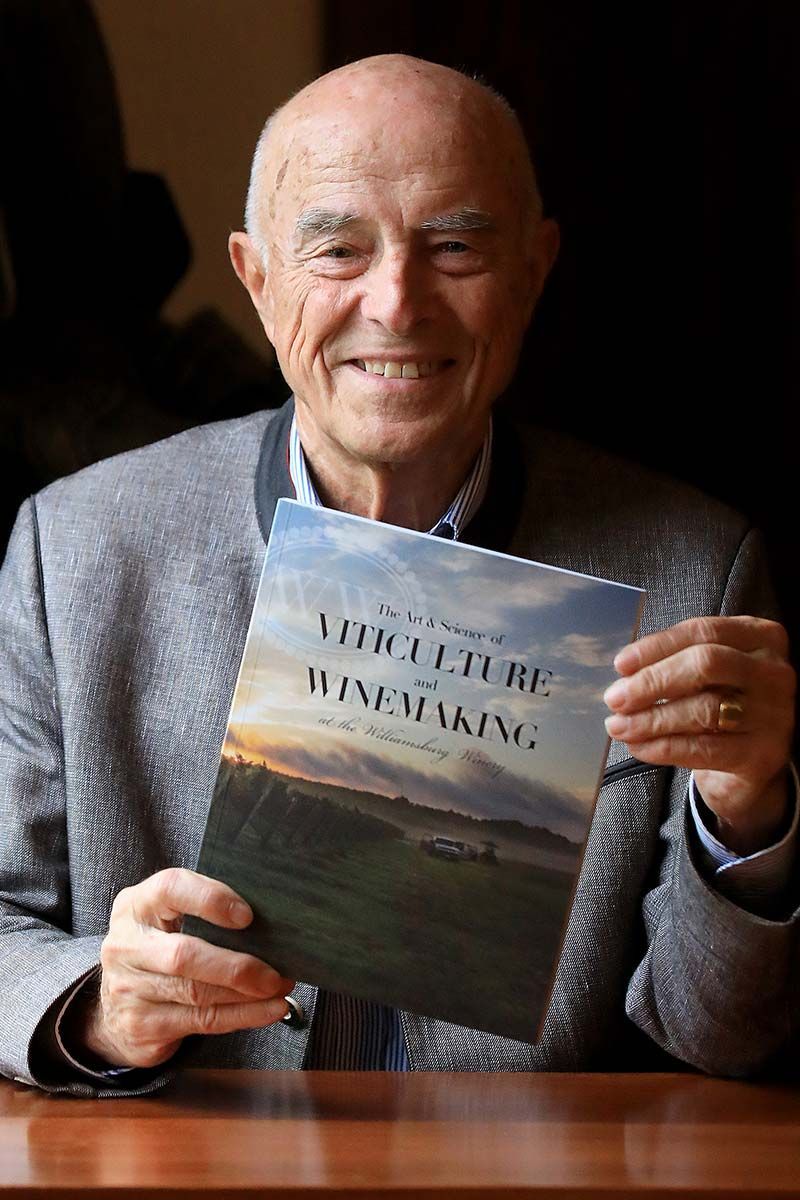

Patrick G. Duffeler, Founder

The Wessex Hundred Black Forest

Ask Patrick Duffeler to choose his most cherished spot on the Wessex Hundred farm or even better, have him take you there. It’s traveling best done in a motorized cart with him navigating the bumpy terrain, whisking past the Chardonnay vineyards, a nod to the deep ravines and flats where the deer often graze in the evening.

You see the spot where you are going long before you arrive, but nothing prepares you for actually being there, inside the Black Forest, where Duffeler returns to his roots with every visit.

Wessex Hundred’s Black Forest is not as famous as the one in southwest Germany where Grimm set many a fairytale. A young Patrick regularly accompanied his uncle and brother into those woods for an adventure. Patrick’s mother also shared her appreciation for nature with her boys, relishing annual outings with them to spy the cherry trees in the spring. Her respect for nature inspired his.

Guide to Wessex Hundred

Welcome to the property of Wessex Hundred. Click on the yellow pins and info boxes to learn more.