Part 19: The (true) Art and Science of Viticulture and Winemaking at the Williamsburg Winery

By the Fall of 1989, we had garnered a few awards. The regional press had been covering the start of our operation and sales were brisk. Looking at the depth of our inventory, we knew that soon we would face a dilemma. In the world of wine, you cannot sell what you do not have in the cellar, and it takes time and effort.

In a similar vein, we had been so absorbed in moving things forward that, though I had had a fair number of years of experience in consumer product marketing, I had failed to focus on the ability to transform concepts into a well structured and developed communication plan with visuals.

Thinking back about the previous three years, it was amazing the amount of information absorbed, the lessons learned. My years in Burgundy might have given me a reasonable perspective on financial issues and on sales and distribution challenges. However, viticulture and winemaking in Virginia was one hundred percent new and proved to be “learn as you go”.

As mentioned in previous Parts, I have always enjoyed drawing. It seemed that one of the ways to convey the coherence of our marketing was to use the Diderot Encyclopedia style of presentation of craftmanship.

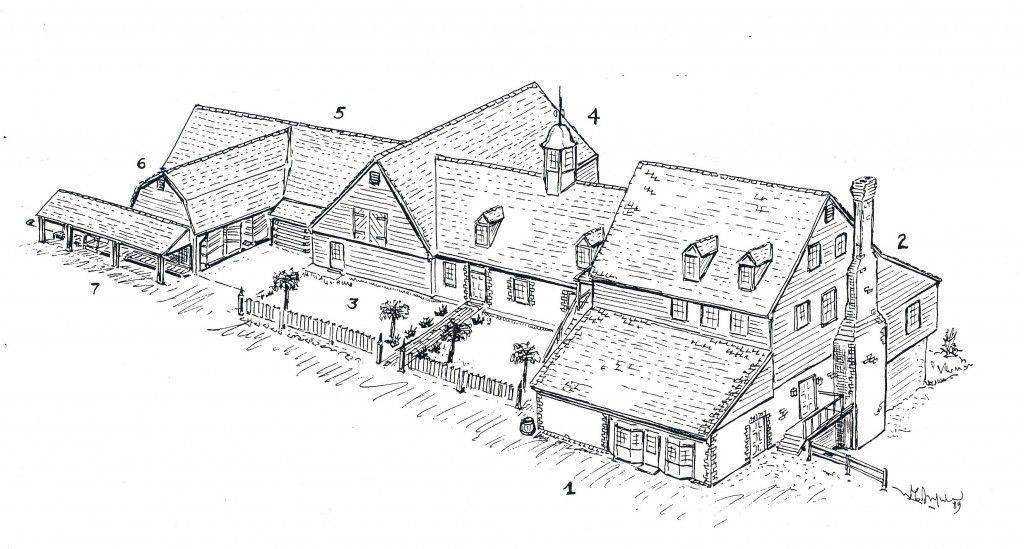

When asked what inspired us in the design of the winery, my answer was that it would be the by-product of the mind of a mad European had he arrived on these shores in the Eighteenth Century. Importantly, it would retain human dimensions by the size of the various buildings to keep it quaint and comfortable.

Already by 1990, the winery consisted of several buildings projecting both that evolutionary step-by-step approach and retaining a village-like charm. It had the character of what the generations of settlers had brought with them from their European cultural background and yet we wanted it all to be very Virginian.

I set pencil to paper and started drawing what viticulture and winemaking was for us. Below is the cover of a brochure which became a very popular hand-out to our visitors.

Front cover of what became a well-received hand-out.

Here follows a quick description of issues that needed to be confronted.

Determining the optimal characteristics for the set-up of a vineyard. Certainly analyzing the characteristics of the soil, its percolation, its nutrients, its micro-biological life. Planning the orientation of the vineyards to the sun, rows running East-West vs. rows running North-South. Plant density and, importantly, selection of a trellising system.

In France, varietal selection, plant density and trellising are determined by the area where you plant your vineyard. The local agricultural agent will ensure that you follow the strict rules.

At the annual symposium for the wine industry in CA, there are always multiple presentations from experts from Australia to Italy, and each advises newcomers to follow their methodology and be assured of great success.

I am prone to giggle about the trellising options. The Italian way could not be more different from the French way and they are both so certain that their system is best that it could almost give rise to cultural warfare.

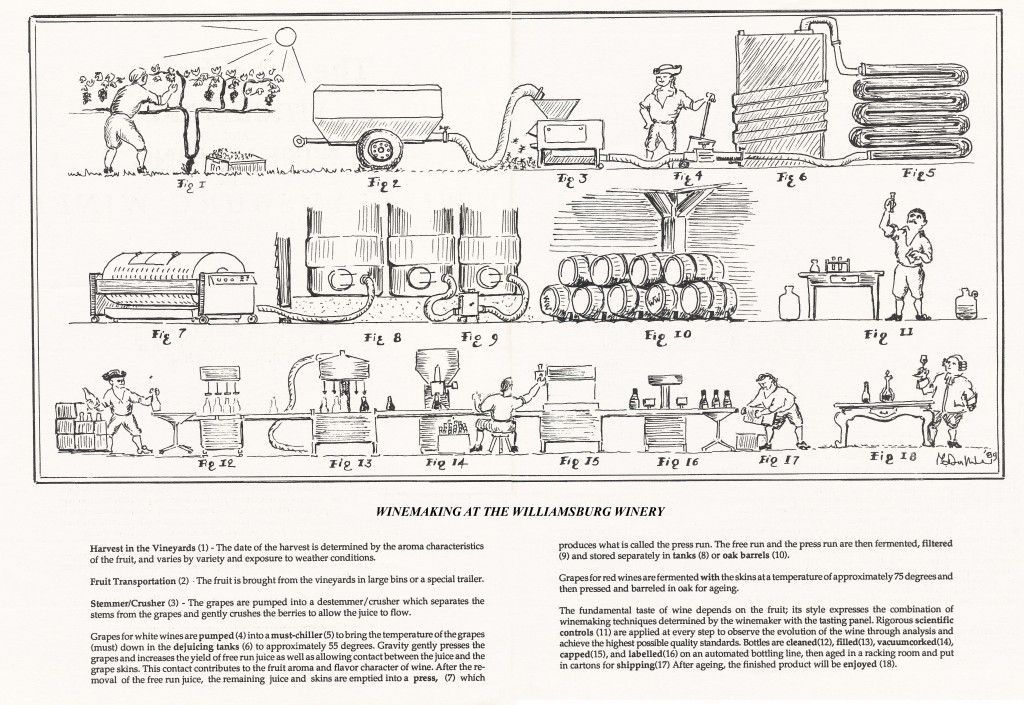

The interior spread describing modern winemaking.

Initially, we had planted our original three acre vineyard with rows eight feet apart. A couple years after she joined us, Jeannette, our Vineyard Manager who had successfully organized the next twenty-five acres with rows ten to twelve feet apart, decided, to my surprise and without prior consultation, to pull every other row in that original vineyard and make it a vineyard with rows sixteen feet apart.

Yes, it gave that much more room for equipment and for air to circulate. Still, today, many new vineyards in Virginia are planted with eight foot spacing between the rows and the debate is inconclusive. It depends on a point of view and personal experience.

After over twenty-five years of vineyard operation during which I witnessed the purchase of pieces of equipment that were to be “critically important” to one vineyard operator only to see it unused by his successor, I have become more pragmatic.

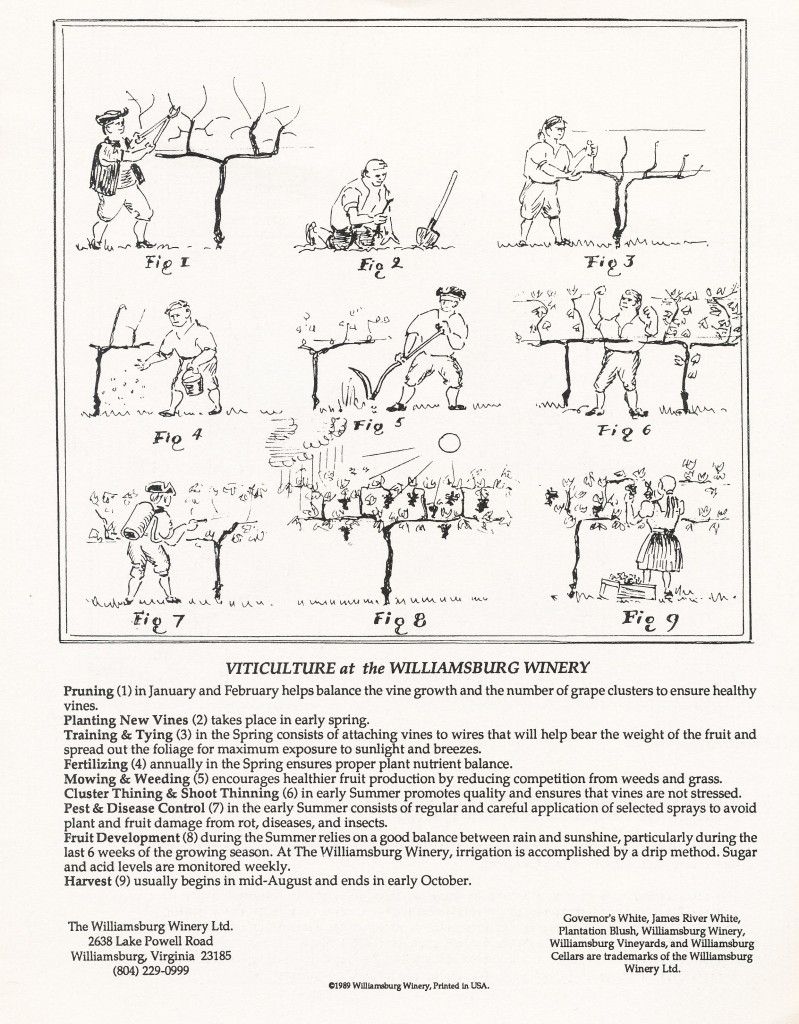

Back cover showing the steps in a year of viticulture.

The same holds true in winemaking. In Burgundy, fundamentally as in all vineyards in the world, you do not necessarily induce fermentation by cultured yeasts. You do not have to. The high concentration of clusters of vineyard in a given area provides plenty of airborne native yeasts present on the grapes at harvest. Thus, fermentation begins naturally in the cellar. The use of cultured yeast is an option for the winemaker in what is available to him to direct the fermentation.

Peggy decided to assist Steven Warner in the barrel cellar. She had been impressed by the reality of the presence of airborne yeasts in our kitchen in France. She would make a whole range of different breads. She would prepare the dough, let it sit in a tray hanging from a beam in the ceiling in a temperature environment of some seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit, and it would rise without the addition of cultured yeasts.

Again, in Burgundy, malolactic fermentation (the secondary fermentation) occurred naturally as opposed to being induced. In this case, the evolution of science has led winemakers to closely monitor fermentation temperature as it deeply affects the extraction of aroma compounds among many factors. Further, it is not common in Virginia to have deep vaulted cellars to provide a constant temperature.

Equally, the new thinking of the ‘70’s and ‘80’s pioneered by Californian winemakers introduced the concept of controlling whether a secondary fermentation is or is not desirable for a given wine, or even whether a partial secondary fermentation is sought for a specific balance between malic acid and lactic acid.

Secondary fermentation control can be a challenge of its own. If the amount of stabilizer used is inadequate, the wine can begin to referment in the bottle and lead to what is called “pushed corks”. In ’88, a small batch of our first chardonnay exhibited corks lifting in the bottle and pushing the capsules up by almost one inch. We popped the corks and re-processed the wine to ensure that it was stable. This was another experience that could have been far more serious.

Steven was open to ideas stimulated by our background in Burgundy. One day, he decided to do the fining of our reds by using the froth of egg whites that had been beaten and gently inserting some in each barrel. I remember Peggy telling me that when they had left the market with some thirty-six dozen eggs, the cashier wondered how large the omelet was going to be. It did do a good job of fining.

About the only thing Peggy was not comfortable with was manipulating empty or full barrels. Talented as she was, her one hundred-five pounds did not measure up. What mattered was that she was elated at participating in every aspect of the business.

From the beginning, we knew that we required a good wine laboratory with the right equipment to help guide the art of the winemaker, but those are only tools. Ultimately, all winemakers agree that a good wine begins its life right in the vineyards. Sound viticultural practices are of paramount importance. Yet, the best vineyard person cannot control the weather. So, it will always be a matter of living with nature.

The extensive studies undertaken by the Geisenheim Institute of Germany with different soils in different climates have underscored that the course of the seasonal equilibrium between sunshine and precipitation and the temperatures will define the suitability of certain varietals to specific climates and the ultimate potential of wines that are harvested in desirable conditions.

Nature can be challenging, but that in itself gives rise to opportunities. For a number of years, the French grew wine grapes in Algeria in weather conditions that were easy and apparently ideal: dry weather avoiding damaging moisture from humidity and plenty of sunshine that brought grapes to rich sugar and tannins. The wines were always described as rough if not just coarse.

In Bordeaux, on the other hand, as in many other areas where the climate is far more challenging, with occasional late spring frost, summer humidity and heavy Atlantic winds, winemakers have pursued the elegance of the right balance between the flavors and aroma compounds to achieve wines of great distinction with color, a pleasant nose, a consistent palate and rich after-taste.

That approach has also been the style of the creation of viticulture and winemaking at the Williamsburg Winery. Today, as we continue to learn and experiment, we feel certain that, as we go further, “The Best is yet to Come.”

(To be continued)

Patrick G. Duffeler

Founder & CEO